A new resource for educators and students, this syllabus explores why feminist leadership still eludes the U.S.—and how we teach toward it.

This is Part 2 of a two-part series on women leaders and feminist leadership. Part 1—out last week—breaks down Angela Bassett’s role as U.S. president in the latest and final installment of Mission: Impossible, and how her representation on screen blurs the line between the impossible fictions and possible realities of women’s power in American politics.

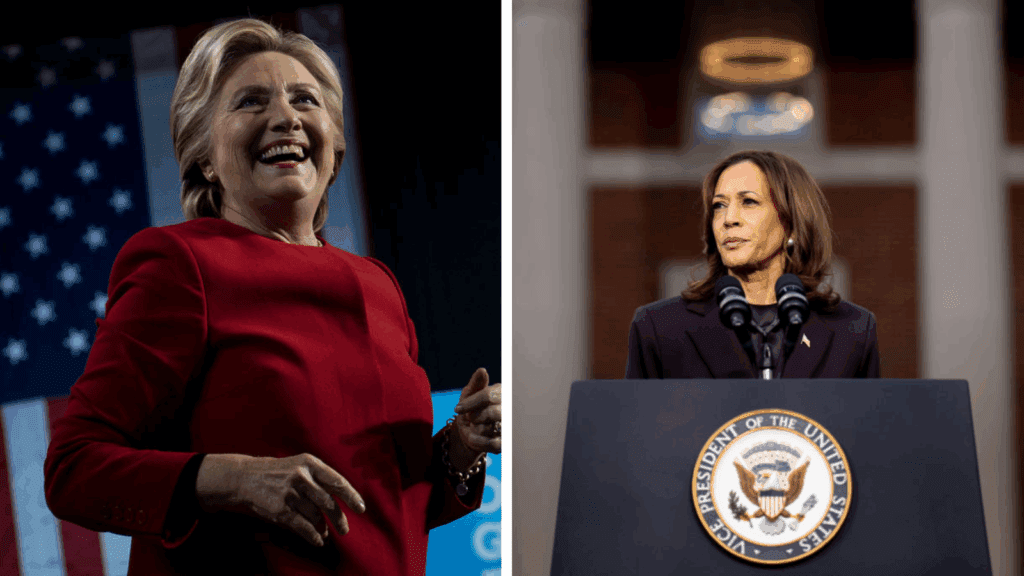

In the last 10 years, the United States came very close to electing our first woman president.

Hillary Clinton—a former secretary of state, New York state senator and first lady—came the closest when she became the first woman nominee of a major political party to run for president of the United States and the first woman to win the popular vote in the 2016 presidential election.

Kamala Harris, who already made history as the first woman and first African American and South Asian vice president of the United States, came up short with a formidable 75 million votes in the 2024 presidential election.

Both candidates were overqualified in contrast to their political opponent—and yet, the U.S. is far behind multiple nations around the world when it comes to electing a woman head of state. (Britannica has an informative timeline of women leaders around the world.) Perhaps this is why few Americans have paid attention to the subject of feminist leadership and feminist governance, which requires more than just electing a woman head of state.

When women assume a position of power, does she represent feminist leadership? Can she govern according to feminist principles? What is the difference between women’s leadership and feminist leadership?

This public syllabus on feminist leadership, assembled by Ms. contributing editor Janell Hobson and students in her graduate research seminar at the University at Albany, is an attempt to respond to these questions by exploring different examples of feminist leaders and feminist movements—both globally (see the world map below) and historically (through key moments and dates). A list of resources for further readings on this subject is also included.

We hope this syllabus can educate us on the kind of feminist leadership that will move us forward toward an inclusive democracy.

Map of Global Feminist Leadership

The following Google Map identifies both feminist leaders and movements around the globe, past and present. (The legend included explains the meanings behind the different color codes and symbols.)

—Authors: Narges Helmisiasifariman and Katherine Owens

Then Versus Now

This segment explores key moments and dates in history as they pertain to feminist leadership.

Hatshepsut vs. Cleopatra: How We Remember Women Rulers

Ancient Egypt is well known for their prominent women leaders, the most famous being Hatshepsut and Cleopatra VII, whose reigns are separated by more than a millennium. However, they are remembered in strikingly different ways, which reveal how gender shapes the stories we tell.

Hatshepsut, who ruled Egypt as pharaoh from 1479-1458 B.C.E., is a lesser-known figure in history. She is largely absent in pop culture or in broad retellings of ancient Egyptian history.

She assumed full pharaonic powers and often depicted herself in masculine form. While European Egyptologists interpreted her actions as attempts to downplay her femininity to legitimize her rule, more evidence suggests this was more likely tied to the religious belief that pharaohs were embodiments of the male god Horus. Hatshepsut’s reign ushered in peace and fostered the growth of trade throughout the region. She is especially recognized for her extensive architectural achievements, including her famous mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri. While her successors attempted to erase her legacy—literally chiseling her image from monuments—modern historians have worked to restore her reputation as a capable and visionary ruler.

In contrast, Cleopatra, the last active ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt from 51 to 30 BCE, is often portrayed through a lens of political scandal and seduction of powerful Roman leaders like Julius Caesar and Mark Anthony. She exists in the cultural imagination as a seductress who used her sexuality to manipulate and even cause the downfall of these great men. These depictions often overshadow her prosperous rule over Egypt, which saw stable economic growth, anti-corruption policies and effective food distribution in times of drought.

Cleopatra’s legacy is filtered through her sexuality and relationships with men, completely overshadowing her political skill and leadership. Hatshepsut literally faced historical erasure and iconoclasm by her successors, removing her from historical memory for centuries to come. Only in recent memory have historians tried to tell her story and the nuances of how she navigated the politics of gender during her life. Both rulers faced different forms of erasure shaped by gendered assumptions about who gets to be a leader and how their history gets told.

—Author: Yumi Cruz

Key Dates in Feminist Governance

- 1878: The International Congress of Women first meets.

- 1911: International Women’s Day (March 8) is first celebrated.

- 1920: League of Nations is established. In the United States, the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution grants women the right to vote.

- 1937: The League of Nations establishes a Committee of Experts on the Legal Status of Women.

- 1948: The United Nations General Assembly adopts the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- 1967: U.N. General Assembly adopts a Declaration on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women.

- 1975: World Conference of the International Women’s Year is held in Mexico City.

- 1979: U.N. General Assembly adopts the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.

- 1993: The World Conference on Human Rights, held in Vienna, recognizes violence against women as a human rights violation. The U.N. General Assembly adopts the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women.

- 1994: The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) becomes a landmark U.S. federal law.

- 1996: South Africa’s post-apartheid Constitution becomes the first in the world to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation.

- 1998: The International Criminal Court is established and has substantive jurisdiction over sexual and gender-based violence and gender-based persecution.

- 2000: The “Color of Violence” conference convenes in California to address the shortcomings of VAWA, specifically examining the intersectional issues of violence against women of color. This leads to the formation of INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence.

- 2007: Nancy Pelosi becomes the first female speaker of the House of Representatives in the U.S. Congress.

- 2008: Rwanda becomes the first country in the world to have a majority-female parliament with 56 percent of seats held by women. Barack Obama becomes the first African American president of the United States and is also recognized as a “feminist” leader.

- 2011: U.N. Human Rights Council adopts the first U.N. resolution on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Thatcher v. Ardern: What Makes for “Feminist Leadership”?

Women’s representation in high-level and decision-making positions doesn’t guarantee a structural change that dismantles hierarchies or redistributes power to achieve social justice. Our modern history reveals that women’s participation in the highest state leadership roles rarely leads to a shift in power and governance dynamics because women’s access to power does not inherently result in feminist leadership. This begs the question: What makes leadership feminist?

The below video addresses this question by comparing Prime Ministers Margaret Thatcher of Great Britain (in power from 1979 to 1990 as Britain’s first female PM) and Jacinda Ardern of New Zealand (in power from 2017 to 2023).

Iceland vs. Liberia: How Women’s Movements Ushered in the First Women Heads of State

Two nations—one Scandinavian and one African—provide excellent examples of how grassroots organizing resulted in the election of a progressive national woman leader.

In the case of Iceland, more than 90 percent of women went on general strike on Oct. 24, 1975, for the country’s first Women’s Day Off (Kvennafrídagurinn) as they emptied homes, offices, schools, factories and more. Organized by the Redstockings and known colloquially as The Long Friday, women took to the streets to demonstrate how their domestic and paid work was indispensable to the island nation’s economy and society, and to protest wage discrepancy and unfair employment practices. Iceland’s parliament passed a law guaranteeing equal rights the following year. The sustained momentum from the demonstration led to Vigdís Finnbogadóttir being elected president of Iceland in 1980, the first democratically elected female head of state in world history. She held the office until 1996.

In Liberia, the nonviolent movement known as Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace mobilized thousands of Muslim and Christian women of all socioeconomic classes in peaceful demonstrations and strikes aimed at ending years of civil war and military coups. Led by Leymah Gbowee, they declared that they would “take the destiny of Liberia into their own hands,” representing the power women as a collective hold in addressing injustice. Their efforts brought about a peace agreement that ended the civil war in 2003. They further mobilized the same movement strategies towards electing Ellen Johnson Sirleaf as the first female president of an African nation. She served from 2006 to 2018 and received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2011 alongside Leymah Gbowee.

—Author: Lisa Witkowski

Further Readings on Feminist Leadership

Nonfiction

Allen, Paula Gunn. The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions. Boston: Beacon Press, 1992.

Boston Women’s Health Book Collective. Our Bodies, Ourselves. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1970.

Brown, Brené. Dare to Lead. New York: Random House, 2018.

Clark, Kim, Jonathan Clark, and Erin Clark. Leading Through: Activating the Soul, Heart, and Mind of Leadership. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2024.

Collins, Eileen M., and Jonathan H. Ward. Through the Glass Ceiling to the Stars: The Story of the First American Woman to Command a Space Mission. New York: Arcade Publishing, 2021.

Cooney, Kara. The Woman Who Would Be King: Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt. New York: Crown Publishing, 2014.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. On Intersectionality: Essential Writings. New York: Columbia Law School Press, 2017.

Gandhi, Indira. Remembered Moments—Some Autobiographical Writings. New Delhi: Allied Publishers, 1987.

Hull, Akasha, Patricia Bell-Scott, and Barbara Smith, eds. But Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women’s Studies. Old Westbury, NY: Feminist Press, 1982.

Kiernan, Denise. The Girls of Atomic City: The Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013.

Merkel, Angela. Freedom: Memoirs 1954-2021. New York: HarperCollins, 2024.

Moronek, Toshio, and Miss Major. Miss Major Speaks: Conversations with a Black Trans Revolutionary. New York: Verso Books, 2023.

Seagal, Lynne. Making Trouble: Life and Politics. London: Verso Books, 2007.

Ware, Susan. Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2019.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects. London: J. Johnson, 1792.

Yousafzai, Malala. I Am Malala: The Story of the Girl Who Stood Up for Education. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2014.

Journalism

Bally, Lorena. “Health, Education and Liberation: 10 Points of the Zapatista Women’s Revolutionary Law“

Buranajaroenkij, Duanghathai. “Political Feminism and the Women’s Movement in Thailand: Actors, Debates and Strategies“

Feminist Action Nexus, “Unpacking the Bridgetown Initiative: A Systemic Feminist Analysis & Critique“

Johns, Steven, “The Iceland Women’s Strike, 1975“

Case study: “Leymah Gbowee and the Liberian women’s peace movement“

Miller, Grace. “The Zapatista Army: A Feminist Revolution Existing Within the Patriarchy“

Perkins, Anna. “‘For us, it is a crises’ Mia Mottley and the Caribbean Revolt against the Climate Crises“

Academic

Agosto, V., and E. Roland. “Intersectionality and Educational Leadership: A Critical Review.” Review of Research in Education 42, no. 1 (2018): 255–85.

Devies, B., and J. E. Owen. Through Feminist Leadership: Navigating Complexities in Leadership—Moving Toward Critical Hope. New York: Routledge, 2022.

Foster, Martha Harroun. “Lost Women of the Matriarchy: Iroquois Women in the Historical Literature.” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 19, no. 3 (1995).

Halley, J., P. Kotiswaran, R. Rebouché, and H. Shamir. Governance Feminism: An Introduction. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Hall, R. L., B. Garrett‐Akinsanya, and M. Hucles. “Voices of Black Feminist Leaders: Making Spaces for Ourselves.” Women and Leadership: Transforming Visions and Diverse Voices (2007): 281–96.

Hill, Margo, and Mary Ann Keogh Hoss. “Reclaiming American Indian Women Leadership: Indigenous Pathway to Leadership.” Open Journal of Leadership 7, no. 3 (September 2018).

Kenny, M., and T. Verge. “Feminist Perspectives on Multilevel Governance.” In Handbook of Feminist Governance, 76–87. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2023.

Kualapai, L. “The Queen Writes Back: Lili’uokalani’s Hawai’i’s Story by Hawai’i’s Queen.” Studies in American Indian Literatures 17, no. 2 (2005): 32–62. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/20737264].

Landsman, G., and S. Ciborski. “Representation and Politics: Contesting Histories of the Iroquois.” Cultural Anthropology 7, no. 4 (1992): 425–47. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/656215].

Niu, G. A.-Y. “Wives, Widows, and Workers: Corazon Aquino, Imelda Marcos, and the Filipina ‘Other’.” NWSA Journal 11, no. 2 (1999): 88–102. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/4316657].

Pankov, Evgeni. “The Issue of Women’s Rights in Iceland: History, Patterns, Takeaways.” October 13, 2023.

Park, Ausra. “Women in Baltic Politics and Leadership.” Foreign Policy Research Institute, December 2024.

Ross, Luana. “From the ‘F’ Word to Indigenous/Feminisms.” Wicazo Sa Review 24, no. 2 (2009): 39–52.

Thame, Maziki. “Woman Out of Place: Portia Simpson Miller and Middle-Class Politics in Jamaica.” Black Women in Politics: Demanding Citizenship, Challenging Power, and Seeking Justice, Julia S. Jordan-Zachery and Nikol G. Alexander-Floyd, 143–64. New York: Routledge, 2018.

Primary Source / Archival

Schulman, Sarah. The Lesbian Avenger Handbook: A Handy Guide to Homemade Revolution (1993)

Fiction

Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. Half of a Yellow Sun. New York: Knopf, 2006.

Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1985.

Benedict, Marie, and Victoria Christopher Murray. The Personal Librarian. New York: Berkley, 2021.

Kidd, Sue Monk. The Invention of Wings. New York: Viking, 2014.

Quinn, Kate. The Rose Code. New York: HarperCollins, 2021.

Sophocles. Antigone. Translated by multiple scholars over time. Various editions available.

Children’s and Young Adult

Free to Be…You and Me, 1972

Bardugo, Leigh. Shadow and Bone. New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2012.

Bolden, Tonya. Speak Up, Speak Out!: The Extraordinary Life of “Fighting Shirley Chisholm. New York: HarperCollins, 2022.

Boulley, Angeline. Warrior Girl Unearthed. New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2023.

Boyce, Jo Ann Allen, and Debbie Levy. This Promise of Change: One Girl’s Story in the Fight for School Equality. New York: Bloomsbury Children’s Books, 2019.

Burnett, Frances Hodgson. A Little Princess. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1905.

Chen, Eva. A Is for Awesome: 23 Iconic Women Who Changed the World. New York: Feiwel & Friends, 2019.

Cocca-Leffler, Maryann. Fighting for Yes!: The Story of Disability Activist Judith Heumann. New York: Abrams Books for Young Readers, 2022.

Collins, Suzanne. The Hunger Games. New York: Scholastic Press, 2008.

DiPucchio, Kelly, and LeUyen Pham. Grace for President. New York: Disney-Hyperion, 2012.

Farqui, Reem. Milloo’s Mind: The Story of Maryam Faruqi Trailblazer in Women’s Education. New York: HarperCollins, 2023.

Halligan, Katherine. Herstory: 50 Women and Girls Who Shook Up the World. New York: Simon & Schuster Children’s UK, 2018.

Harrison, Vashti. Little Leaders: Bold Women in Black History Month. New York: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, 2017.

L’Engle, Madeleine. A Wrinkle in Time. New York: Dell, 1962.

MacMillan, Kathy, and Manuela Bernardi. She Spoke: 14 Women Who Raised Their Voices and Changed the World. New York: Workman Publishing, 2019.

Maas, Sarah J. A Court of Thorns and Roses. New York: Bloomsbury Children’s Books, 2015.

Murray, Jenni. A History of the World in 21 Women. London: Oneworld Publications, 2018.

Rappaport, Doreen. Wilma’s Way Home: The Life of Wilma Mankiller. New York: Disney-Hyperion, 2019.

Russell, Anna. So Here I Am: Speeches by Great Women to Empower and Inspire. London: White Lion Publishing, 2019.

Schatz, Kate. Rad Girls Can: Stories of Bold, Brave, and Brilliant Young Women. New York: Ten Speed Press, 2018.

Todd, Traci N. Stacey Abrams and the Fight to Vote. New York: HarperCollins, 2022.

References

Anderson, Marnie. “Kishida Toshiko and the Rise of the Female Speaker in Meiji Japan.” Academia.edu, June 4, 2015.

Cooney, Kara. The Woman Who Would be King: Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt. NY: Crown Publishing, 2015.

Erkan, A. Ülker. “The Formation of Feminist Identity: Feminism in the 1930s Turkey and Britain.” Kastamonu Education Journal 19, no. 3 (2011): 1013–28.

Lanfranchi, Sania Sharawi. Casting off the Veil: The Life of Huda Shaarawi, Egypt’s First Feminist. London: I.B. Tauris, 2015.

Parmar, Shubhra. “Feminist Awakening in Rwanda.” The Indian Journal of Political Science 74, no. 4 (2013): 687–98. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/24701165].

Sawer, Marian et al. Handbook of Feminist Governance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2023.

Special thanks to our University at Albany librarian Deborah Lafond for her research assistance.