World Music Day: How craftspeople in Maharashtra’s Miraj town are using GI tag to bring tanpuras, sitars in every home

For centuries, Miraj handcrafted string instruments for musicians across India. Now, as the handmade gives way to machines, this town in Maharashtra hopes to redefine its legacy and renew its place on the classical music map

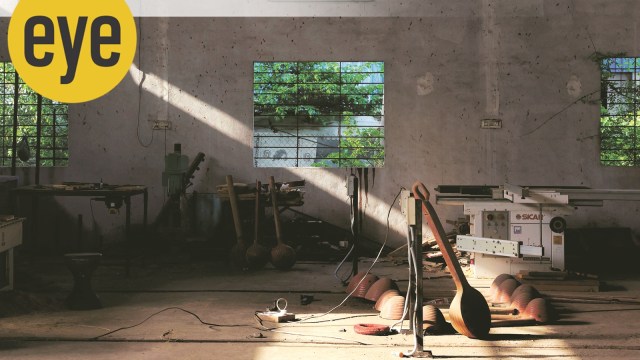

A workshop in Miraj (Express photo by by Amit Chakravarty)

A workshop in Miraj (Express photo by by Amit Chakravarty)As a child of the legendary vocalist Pt Bhimsen Joshi, Shrinivas Joshi didn’t need to be introduced to music. His mother, Vatsala Mudholkar, was also a classical singer, though not a performer. From his birth, Shrinivas saw tanpuras in the house where they were living.

“The instrument is of prime importance to classical vocal music. Just as a painter needs a canvas, a classical singer must have a tanpura. I learned singing while playing a tanpura sitting in front of my father like his other disciples,” says Shrinivas, who lives in the old house, Kalashree, in Pune’s Navi Peth.

His tanpura has come down from Ustad Abdul Karim Khan, the revered founder of the Kirana gharana, and was gifted to Bhimsen by the veteran vocalist Hirabai Barodekar. He owned four other tanpuras, one pair in Mumbai and another in Pune.

“All our tanpuras have been made in Miraj. Ustad Abdul Karim sahab lived there and studied the optimal dimensions of the instrument with the craftsmen. He left behind inputs on how it should be constructed. Tanpuras are made in north and south India as well as in Bengal but, from what I hear, Miraj tanpuras are much in demand. The craftsmen regard each tanpura as a living being, with a soul and associated myths. I feel blessed and fortunate to be playing such an instrument,” says Shrinivas.

100-year-old Ahmedsahab Sitarmaker who made twin tanpuras for Ustad Ghulam Ali Khan, Pt Bhimsen Joshi and Gangubai Hangal (Express photo by by Amit Chakravarty)

100-year-old Ahmedsahab Sitarmaker who made twin tanpuras for Ustad Ghulam Ali Khan, Pt Bhimsen Joshi and Gangubai Hangal (Express photo by by Amit Chakravarty)

Hidden sounds of heritage

For almost 200 years, tanpura, sitar, sarangi, veena and other string instruments have been handcrafted by the artisans of Miraj and sent to all corners of India. Made from bitterly-inedible pumpkins that grow in two farms near Pandharpur and red cedar wood from Karnataka, the instruments are characterised by a rich and resonant sound quality. More than 300 tanpuras and an equal number of sitars are made here annually. The craftsmen are custodians of generational knowledge, who work unheard, unseen and unapplauded, surviving battles that are fought by the invisible.

Located around 400 km from Mumbai, Miraj, a former princely state, lies in the sugarcane belt of Maharashtra’s Sangli district near the border of Karnataka. The road to the town passes through lush fields that rustle in the breeze after the first monsoon showers, hills that fade into the horizon and gurgling streams under an overcast sky.

Beauty becomes more difficult to find on reaching Miraj. The town’s other flourishing identity looms large — hospitals, pharmacies and health centres, sometimes, a dozen in a row. Miraj wears the label of being a medical tourism hub more than its musical heritage. The creators of musical instruments occupy a small neighbourhood that branches from the arterial MG Road. This is Shaniwar Peth, home to Sitarmaker’s Galli, where one can find any number of people with the last name of Mirajkar or Sitarmaker.

Young men are bent over instruments in workshops that open onto the street (the idea of women artisans has not caught on in two centuries). These men have learned their skills sitting at the feet of family elders through the guru-shishya parampara. They can intuit how thick or thin a pumpkin or wood should be to create a full sound when an artist plucks the strings. Making a tanpura requires groups of six or seven men to work together, one carving the wood, another shaping the pumpkin, a third attaching the parts while the rest polish, paint, design and fix the strings. The surest sign that you are among artisans are the dry pumpkins that cover the workshop ceiling like bubbles. Under it, tanpuras, sitars and veena in different stages of production stand sentinel against walls.

To hear the missing sounds of Miraj, visit at night. After the riders and the motorists have left, the maestros among craftsmen, who feel the vibrations before others can hear it, begin to tune instruments. As the notes of Raag Desh, Charukeshi or Bhairavi drift through the darkness, you know that an instrument has been born into the world.

An artisan at work (Express photo by by Amit Chakravarty)

An artisan at work (Express photo by by Amit Chakravarty)

Back in the past

The 650-year-old dargah of the Sufi saint, Khwaja Shamsuddin Meerasaheb, is the spiritual nerve of Miraj, whose devotees range from sultans of the past to present-day crowds. After the kalash of the dargah was damaged in the 1800s, the ruling Bijapur Sultanate ordered its best weapons makers to carry out repairs. Among them was Ahmedsaheb Shikalgar, who settled down in Miraj and whose descendants continued to make weapons for the army of Bijapur Sultan Adil Shah. Masters of swords and artillery, they acquired the name of shikalgars or weapons makers. The sophisticated guns that arrived with the British pushed the shikalgars into the shadows.

What were they supposed to do? The answer came when the Patwardhans, the ruling family of Sangli, organised a soiree for an important vocalist from modern-day Pakistan. Before the show, the maestro’s tanpura broke. Enquiries were made but they could not find a karigar to repair the instrument. Word reached the Patwardhan ruler of Miraj, Shrimant Balasaheb Patwardhan II. A patron of the arts, Shrimant Balasaheb sent the tanpura to two shikalgar boys whose hands were said to hold extraordinary magic.

They were the brothers Mohiddin and Faridsaheb, the sixth-seventh generation of the line of Ahmedsaheb. They not only repaired the instrument but did it so well that the visiting vocalist gushed that the sound was superior than before. Since then, there have been musical instrument makers in Miraj, with the present craftsmen tracing their ancestry to the two brothers. That the hands that made weapons of war could just as easily create instruments of music holds a parable for the world today.

There is only one workshop in Miraj, Jai Hind Musical House and Dhaar Centre, where one can still meet artisans who are, at once, sitarmakers and shikalgars. You can buy a Bhajan Veena while getting your kitchen knife sharpened.

Mohsin Mirajkar was instrumental in getting the GI tag for the Miraj sitar and tanpura in 2024 (Express photo by by Amit Chakravarty)

Mohsin Mirajkar was instrumental in getting the GI tag for the Miraj sitar and tanpura in 2024 (Express photo by by Amit Chakravarty)

The old legend

Several times a day, a tall figure can be seen walking through the streets of Shaniwar Peth. His kurta-pyjama is as white as his beard and hair. Ahmedsahab Sitarmaker, who turned 100 last year, is a living legend. He has been working since he was nine, never been to school but learned from his father and uncles.

Ahmedsahab made Ustad Ghulam Ali Khan, Pt Bhimsen Joshi and Gangubai Hangal their twin tanpuras. The three tanpuras that accompanied Begum Parween Sultana were his creations. Ahmedsahab decided to hang up his tools when he turned 96. “After that, my shoulders and arms began to ache. It was so unbearable that I went to an orthopedic doctor. He told me, ‘Dawa nahin chahiye. Kaam chalu karo (you don’t need medicine, get back to work)’. Now, I don’t have BP, sugar or any other ailment,” says Ahmedsahab.

He draws a heavy block of wood close and begins to chip away with a chisel and hammer. His arms move with force and grace. In no time, the formidable block has been tapered in the shape of a plate that will cover a tanpura. Ahmedsahab will keep working until it is finished. “My chacha once gave me a tight slap because I had made a mistake with the strings. Our craft has been inherited from a long line of ancestors and we carry a lot of responsibility. Kaam ka koi timetable nahin. Kaam poora hone tak, khana khane ka nahin (Our work doesn’t have a schedule. Until our work is finished, we don’t eat),” he says.

Dry pumpkins on a workshop ceiling (Express photo by by Amit Chakravarty)

Dry pumpkins on a workshop ceiling (Express photo by by Amit Chakravarty)

…And the new

Miraj once had almost a thousand craftsmen; today, there are 150-200 left. Workshops have been rented out or sold. It takes around 15 days for a team of six to make a tanpura. An artisan spends six years before he can understand the craft. For all the effort, a women’s tanpura starts selling at Rs 25,000 while a men’s is upward of Rs 35,000. The base price for a veena is Rs 25,000 while a sarod starts at Rs 30,000. “If we increase the prices, who will buy? After deducting the cost of raw materials, we are left with around Rs 2,000-Rs 3,000 per instrument. Pet ki bhook mitaney ke liye kaam karte hain hum (We continue to work to stay out of poverty),” says Mohsin Mirajkar, the sixth-generation tanpura maker.

Mohsin, in his forties, is the savvy modern face of Miraj sitarmakers. A craftsman who is also a trained classical musician and a graduate, Mohsin was instrumental in getting the GI tag for the Miraj sitar and tanpura in 2024. This has safeguarded the unique identity of the Miraj instruments and located it in its geography. “The boys who inherited the art form are leaving for other professions as this is labour-intensive work with little profit. There will not be sitarmakers in Miraj in 20-25 years unless we act now,” he says.

The number of tanpuras made in Miraj is only a third of the orders received annually. Orders for sitars are 700-800, of which less than half are produced. “There is a huge backlog,” says Mohsin, adding that the introduction of music departments in college since Independence has increased interest among people. Mohsin’s family runs the 100-year-old Indian Musical Shop. He has had a lot of opportunities to leave Miraj. “But, I feel that my life’s purpose is in Miraj,” he says.

“Our plan is to standardise instruments by size and shape. Artisans shouldn’t be using their physical effort to hollow out the wood or cut designs for hours. These can be done by machines within minutes. With standardised parts created by machines, we can assemble tanpuras, sitars and veenas faster and increase productivity and revenue. We can reach more buyers. Our craftsmen will get relief from physical labour while making more instruments. We will have funds for the older artisans who are suffering from lung, eye and back problems from the work,” he adds.

Mohsin’s dream project is housed in the Sangli-Miraj Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC) area, three km away from his home. Behind a chain-mail fence stands the beginnings of the ambitious Miraj Musical Instruments Cluster. It is a 4,000 sq ft workshop and a lot of empty land for which Mohsin has prepared plans. “This is going to be the only centre in India working towards mechanising the tanpura and the sitar, thus standardising the product but also training future artisans and musicians, including women,” says Mohsin.

He had been working on the project plan for four years when the state government announced the Maharashtra Industrial Cluster Development Programme in 2016. He submitted a proposal, which was accepted in 2019 and the state sanctioned Rs 2.32 crore of which Rs 70 lakh has been disbursed. The centre made a notable stride last year by training 40 women under the state’s Entrepreneurship Development Programme. “Six or seven of the women have started business in musical instruments,” says Mohsin.

The total cost of the project is Rs 3.50 crore, which will include a research centre, training centre for making and playing instruments and recording but the cluster has run out of funds. “The project is very important for Miraj and the country’s larger music industry. It is my dream to see a tanpura in every home, and it will happen,” he says.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05